Scopri il MEtA Museo:

– The Upper Seriana Valley Museums

– Woodcutters and Coal Miners

– Miners’ Hall

– Spinning and Textiles Hall

– The Rural House

– The Farmer’s Work

– The Rasga del Tönöla

Established in 1982, the Ethnographic Museum of the Upper Seriana Valley is divided into four sections and it analyses the secular relationship between the territory and the activity of the valley population with reference to spinning, the work of coal wokers, bricklayers, woodcutters and miners.

It presents documents that go through the history of the silver mine which exploits the discovered deposit in the XIth century and which made the country famous. It includes an interesting historical cartography, tools and reconstructions of how life was in the mine. Near the museum seat, there is a house built in the fifteenth century, it offers an environment of how domestic life, artisanry and mountain agriculture were at the time.

The foundation and personality that built it

The Ethnographic Museum of the Upper Seriana Valley was established with resolution n.31 of 25 April 1982. The first programmed initiative goes back to December 1982, an exhibition of ancient photographers on the theme “Man and the environment in the Upper Seriana Valley” besides another publication with the same title taken care of by Pino Cappellini, a journalist of Eco di Bergamo. A second exhibition, dedicated to the mines and to the miners of the Upper Seriana Valley, then consented to collect materials and documents used after that for the preparation of a specific section of the ethnographic museum. In the context of the proposed initiatives, a conference was held in the council chamber of the Municipality of Ardesio on 9 June 1984 on the theme of the mines of Seriana’s valley. The meeting saw the partecipation of technicians, scholars and various personalities, amongst which were Galli, Councillor for Culture of the Lombardy Region. The museum originally found its location at the Sanctuary Square, in the old renovated building called “home of the pilgrim”, on loan for use by the Parish of St. George the Martyr of Ardesio.

Historical names or contractors who took care of the setup of the museum and the manuscripts

The main proponents of the museum were: the mayor Guido Fornoni, the Councillor for Culture Elisabetta Fornoni, the geologist Dott. Daniele Ravagnani who directed the museum since its birth and not in 1995, Luigi Furia of Gorno, Giampietro Olivari, the mayor Attilio Bigoni and many more. A special mention goes also to Mrs. Claudia Zucchelli.

Luigi Furia, besides taking care of the setup, took also care of the first publications: “Mines and miners”, “Spinning and textiles from other times”, “The Coal diggers and the woodcutters”. The furnishing and the publication of the fifth and sixth section, called “The Rural House” set in the old building of Tasso Street and “La calchera” the ancient process of producing lime, were set up in the river park (museum is dispersed), from the then mayor Guido Fornoni with the collaboration of Prof. Angelo Pasini (later curator of the Museum)and from Prof. Martino Bana.

There are dozens, maybe hundreds of people who have contributed to the construction of the museum through donations of objects and through collaboration for the setup. The collection’s origin has mostly been found in the localities of the Upper Serian Valley and Scalve Valley, with the help of collection of pieces from research campaigns. The collection on the mines on the part of Prof. Luigi Furia and the acquisition of the technical office of the mines of Valle del Riso from the part of the geologist Dott. Daniele Ravagnani is significant.

Discover the MEtA Museum:

The Upper Valseriana and the Museums of the Upper Valley

The Upper Seriana Valley

A valley of a million faces and landscapes: mountains and peaks, streams and lakes, plateaus and valleys,villages, towns and a river, il Serio. Nature and the imprint of man have given life to a millenial story which still exists today since prehistoric times,

The valley winds for around 50 kilometres along the river path of the river Serio, with a Mountain Community that develops from Valbondione to the city of Bergamo, including the Municipality of Ranica. But the Upper Valley is a different world with respect to the urban area. An area which is more preserved and largely unchanged: here certain traditions and jobs have been handed down over time, but today the risk of losing all this cultural heritage, even materialistically, is a real risk. This makes it, therefore, necessary to rediscover this territory and its past in a participative and multi-dimensional experience.

The Rural House

A few minutes from the museum, in the direction of the centre of town in a fifteenth century house, there are settings of domestic life, of artisanry and of mountain agriculture. In order to rediscover the lives of the ancestors, one is obliged to pay a visit: one relives a piece of history, with authentic objects and the daily atmosphere of the farmers from the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The Museums of the Upper Valley

The MEtA is being suggested as a point of reference for the museum offer of the Upper Seriana valley.

Which harvests can be visited here in the surroundings to learn more about gastronomy?

At Ponte Nossa there isil Maglio, to see on site how in the past men worked with iron and how they forged various useful objects. Then Gromo, going back up the valley, where the Museum of the swords and parchments constitutes a rich stage of historic fascination.

At the end, one should not miss a visit to the city of Clusone, to discover the collections of MAT – Museo Arte Tempo (Museum of Art and Time), with its pictures and its mechanisms of tower clocks.

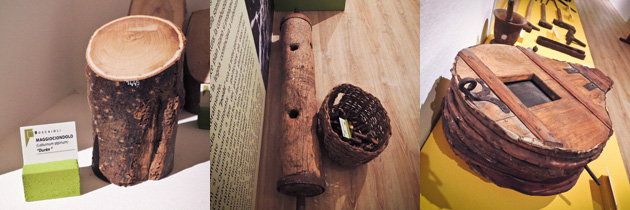

The Hall of the Woodcutters and the Coal Miners

The Forest: A green mine

The forest was always considered a “green mine” from which one could collect various useful products: firewood, coal, wood for construction. Even in the Upper Serian Valley, the woodcutter was an expression and a witness of the old soul of the community: today, there are only a few left; once whole subdivisions lived in and from the forest. With them, there were also the coal workers, who today perpetuate the ancient and mysterious rite of “rito del poiàt”.

These men had to often stay for months and months in the forest: their lodging was a shack made of branches and bark, their food was polenta and little else. Time was marked with the sky: they worked from “stèle ai stèle” (from star to star), even fourteen hours a day.

Every woodcutter had his own tools for the job, which he carried around with him, even when he happened to work away from home. The trees were cut only with the axe; then the branches were cut from the trunk with the “sgùròt”.

Resin Machine

Another job tied with the forest was that of the “rasì”, the one who took care of the production and elaboration of the resin. It was collected at the end of Summer, it was made to boil in big pots and, still hot, it was poured into the “machina de pòrga la rasa”, a machine to purify liquid resin. When it was purified like this, it was used to prepare medicinal products and glues, whereas kids gave it fire to let it pour and then chew it.

Transport of Timber

In Autumn, the tree trunks had to be carried to the valley. For a short while, they were dragged from the same woodcutters, for longer journeys mules and horses were used, or they let them flow in the “sòènde” (canals made by the trunks themselves) and in the “trinai” (canals carved into the snow).

Firewood was transported on the shoulders, with the mules, or else with the cantilevered wires. A big metal wire was stretched between two points (socalled stations) at different levels; the trunks were hung there with pulleys and they made them slide down the valley.

On the other hand, the transport of coal was left to “portì”, women and youngsters who loaded their shoulders with big sacks, even carrying a fifth of the load. No mules or “preàle” (sledges) were used to avoid that the coal could break or crumble and thus resulting in the loss of weight and value.

The “Poiàt”

Once the big logs were removed from the forest, it was then the turn of the coal workers. A tall pole of around 2.5 metres was planted in the centre of a tall clearing and around it short pieces of wood were placed to build a sort of square fireplace. Around this, trunks and branches were rested, slightly inclined, to create several thinner layers on the outside. The accumulation of wood was at the end covered with leaves and soil.

At this point, the central pole was removed and the “poiàt” was ready to make charcoal.

It was lit by throwing embers into the hole that was left free by the pole; a little at a time, small branches were introduced one by one to encourage the fire, then it was closed with a clod, drawing a cross on the top. This was how the cooking phase was introduced: the embers slowly rose, then the wood started to get carbonized while expanding to the side. The average duration of a “poiàt” was seven days and it was continuously monitored.

After two days, small vents began to be made starting from the top. When blue smoke came out of these, it meant that the coal was ready, so it was corked while others lowered it down, until it reached the ground.

Finally, whilst paying attention that it did not catch fire, the coal was mined.

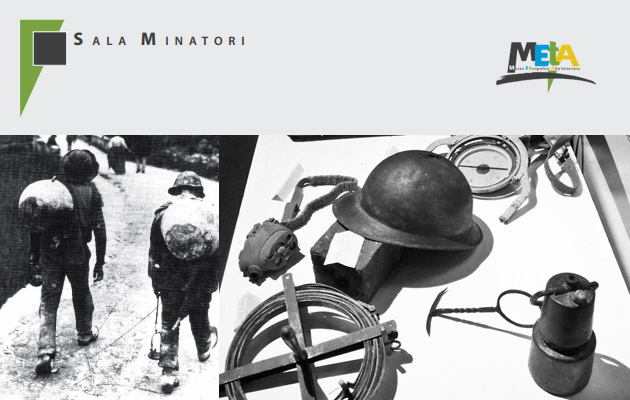

Miners’ Hall

Mines in the Upper Seriana Valley

The depths of the mountains of the Upper Seriana Valley are crossed by kilometres of centuries-old tunnels and galleries. Thanks to the find of a “foundry deposit” at Parre, which happened in 1883, we have proof that man started mining activity more than 3000 years ago. The primitive peoples could look for minerals only where the rock benches flourished on the surface and the mountainous zones were an ideal environment. The activity tied to the mines was therefore the first moment of civilization of the mountain valleys.

Work in the Mines: The Cultivation

The works for extraction from the mines are called “cultivations”.

At the end of the nineteenth century, before the arrival of foreign people (the English and the Belgians), who introduced avantgarde mechanisms and tools, work was done with rudimental methods and means. The mineral was excavated starting from the flourishments, therefore from the top to the bottom; subsequently, through tunnels that went down, the cultivation started from the bottom upwards.

Levers and picks were used to break the rocks; later, there was hand-drilling with a mine-chisel, whose holes were filled with dynamite in sticks. Starting from the 1920s, drilling machines with compressed air were finally introduced.

The Wagon and the Sorting Process

To transport the mineral out of the tunnel, there were boys who used iron pots and pans. Subsequently, the “carreggio” was introduced, which is the transport with wagons on tracks, pushed by hand or towed by mules or horses; following that, locomotives, which were able to tow numerous wagons, were introduced.

On the “square” at the entrance to the tunnel, there were “taissine”, women in charge of sorting the mineral, helped by some boys called “galecc”, and the blacksmith who resharpened mine irons subject to easily deteriorate due to the hardness of the rock.

Transport from the Valley and Processing

Transport to the valley happened on the shoulders or with special sledges towed by the “strùsì”, then by wagons to reach the ovens. Special cableways with pulleys were installed only at the end of 19th century. Small wagons were made to slide exploiting the force of gravity.

Both the iron and the zinc mineral were cooked in special ovens, the former to make it more crumbly before sorting it; the latter to make it lighter and facilitate its transport.

For zinc and iron, the ovens were then replaced by buildings, in which the minerals were grounded and floated with water and chemical agents to separate the metal from sterile material.

Melting Furnaces and Forges

The mineral mixed with coal was put in ovens for melting. The liquid iron which came out was cast in special containers to make cast iron ingots in various forms. The cast iron then passed to the forges where, after turning red-hot, it was processed.

On the contrary, the zinc mineral was exported abroad or sent to other parts of Italy for further processing. This was happening until the “blast furnaces” of Ponte Nossa were put in production in 1952.

The Mine Workers

Different people are attached to work in the mines besides that of the most well known, the miners. The “caporàl” was the one who supervised the cultivation, controlled the quantity and the quality of the extracted mineral and kept in touch with the management.

The “foghì” with his box full of dynamite, detonators and fuses, went from one construction site to another to blow the mines; on the other hand, the work of the “wagonist” consisted in pushing the wagons of minerals up and down the mine. At the entrance of the mines, one met the “taissine” who separated the mineral with special hammers from the other substances. The“strùsì” towed sledges full of minerals to the valley, until they were replaced by the “frenòr”, who had to stop the little running wagons in the cableway stations. The “flotadùr” was the one responsible for the cells of the washing house where the minerals were floated.

The Geological Study

The main operation that was necessary to do before starting to dig was the geological study of the area. With the help of a number of investigations with geophysical methods (magnetic, gravimetric, electric…) and mechanical prospecting (trenches, wells, boreholes …), the extent and power of the mineral layers were ascertained even to determine the purpose for economic reasons.

In those times, the only possible research was that done by sight. It is for this reason that the older mines are found in the mountains, along streams of water or in desert areas where the rocks are not covered with arable land.

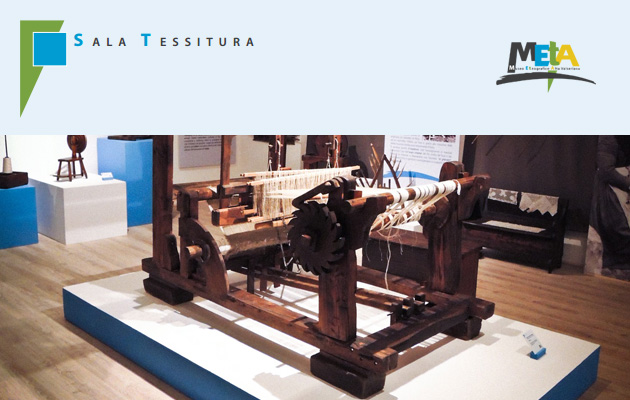

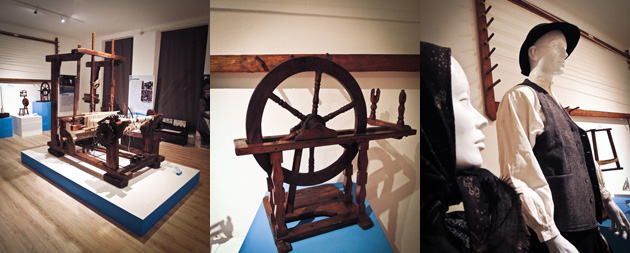

Spinning and Textiles Hall

The cultivation of flax and hemp

The former landscape of our mountains was characterized by small blue rectangles of linen, green of hemp or blond of wheat and barley. Linen and hemp were essential for the production of textiles and fabrics.

The cultivation of flax took place in the flatter stretches: after having “sapunàt e sapàt”, or hoed, the field was sown. When it reached maturity, it was collected and dried; then it was freed from the seeds by beating it with a special wooden mallet. The cultivation of hemp was similar to that of flax and, when it reached maturity, it was uprooted stem by stem.

Maceration and Kneading

After husking, the flax and hemp were spread out on the ground outdoors, exposed to rain and sun for a few weeks until the external rind was completely macerated; they were then left to dry and dry, then crushed. The flax was beaten with a wooden mallet, the hemp was worked with the malaxer (srantòia) to free the fibers from the bark.

Combing

To eliminate the fragments of bark and make the fibers soft and elastic, we proceeded to the spatula. The spàdola was a kind of curved wooden saber that was passed and passed over the fibers stretched on a special board.

The combing freed the fibers of the last impurities and thinned them. Special combs (spinàs) with sharp pyramid-shaped nails were used; generally three types of combs were used, of different sizes and with denser teeth, to allow gradual work.

Wool Production

The presence of shepherds and their flocks, whose activity was linked to the processing of wool, was widespread.

After shearing, the wool was subjected to a first selection “by sight” to separate the short wool from the longer one. After that, the wool was washed. To degrease it, the wool was soaked in tubs with hot water and ash, moving it around with sticks for around fifteen minutes. To rinse it, it was placed in wicker baskets with running water. Finally, it was stretched out in the air to dry.

Beating and Oiling

The wool was therefore “vergata”, that is beaten with flexible wooden rods to clean it further and sprinkled with linseed oil to increase its elasticity and resistance. At this point, the wool destined for the warp thread was combed, the weft wool was stripped. Combing. The wool, which was divided into little tufts, was worked by rubbing it between two combs to thoroughly eliminate impurities, align its threads and obtain a smooth and regular yarn. Carding was practised for short fibres. After having shredded the wool by hand and soaking it in water and oil, it was worked with the card, a tool equipped with steel teeth, which made it softer and homogenous.

Spinning

In spindle spinning, the spinner took a small amount of material to be spun from the spool (a stick that held the mass of fibers), it was fixed to the upper end of the spindle and made it whirl around on itself. In doing this, the thread twisted and stretched.

With the spinning wheel instead (carelì de filà), a pedal was pressed that set the wheel and the spindle with wings in motion, connected to each other by a cord. A piece of fiber was attached to a spool threaded on the spindle and the rotation of the fins made them twist forming the thread.

We then moved on the destemming, that is, winding the thread unwound from the spindle or spinning machine into skeins (through the use of the rotating reel). The skeins were then unravelled with the spinning wheel (ol ghéndol), wrapping the thread in balls or on pieces of (winding).

Weaving

The yarn is now ready for weaving: the first phase is the warping. It was necessary to pass the necessary threads around the pegs of the warp several times to form the warp of the desired height. Then came the sizing: the yarns were impregnated with gluey liquid obtained from the boiling of animal skins which gave them greater consistency and resistance. Finally the beam warping consisted of arranging the individual warp turns one next to the other, on the beam (part of the loom), in order to then move on to the processing with the loom.

In the hand loom, the weaver, using the pedals, imparted a “raising” and “lowering” movement to the warp threads. Placing the threads in the half lowered and half raised position, the weaver pulled a shuttle containing a spool of yarn, called weft, and made it arrive to the other end of the loom. Then he changed movement and position of the warp threads and repeated the push of the shuttle in the opposite direction. In this way the weft crossed with the warp, forming the fabric. Then it changed movement and position of the warp threads and repeated the thrust of the shuttle in the opposite direction. In this way, the weft crossed with the warp, forming the fabric.

After weaving, the linen and hemp had to be washed with water and ash and then exposed to the sun and wet continously, thus becoming whiter and softer. For the wool, the procedure involved different phases, first of all the purge. The fabric was scraped off with knives and clothespins and treated with hot soapy water. While full, the cloth was subjected to various compressions in conditions of humidity and heat, making the filaments weld together, thus becoming compact and thick. After these operations, the fabric was wrinkled and irregular in size. It therefore had to be dried under pressure. It was then taken to the wooden frame (ciodéra), a series of wooden crosspieces on which it was pulled through special mechanisms. The finishing continued with the brushing (a frame with vegetable thistles was swiped on the damp fabric) and the topping (the height of the cloth was equalized with special scissors). With painting, ironing and packaging, the finished product was reached.

The Rural House

In the old fifteenth century building “ca’ della Murinina” the fifth museum section is set up with settings of rural culture. Open to the public on a daily basis, the rural house is situated in the medieval town that is discovered through the streets that lead to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Grace.

The rural house

The Museum was housed in an ancient rural house dating back to the fifteenth century. From the outside it is possible to notice a medieval stone portal, whereas in the inside one can see the vault with the classic “sìlter” shape, with a typical window with grating.

From the street level, you enter the kitchen, the main room of the house with the fireplace used more for cooking and for processing milk than for heating.

The fireplace compartment is equipped with all the necessary iron tools: the chain for hanging the pots (sòsta), the tripod (tripé), the grill (graticola), the shovel (bernàs), the pliers (moèta).

On the mantelpiece there are jars of salt (sal), pepper (pìer), matches (solfanèi) and even before that the flint, the sugar (sőcher), the mortar (mortér), lume (oil lantern or lőm ad olio) and the polenta stick (rősgadùr).

Next to the fireplace we find a shelf equipped with iron hooks where are hung: pots (pignàte), lids, buckets,copper; while on the side the “shelf” is hung on the wall, where the soup plates and plates, the wooden bowls (basgiòtt)and the other dishes are placed.

Against the wall there is a crate divided by two compartments: one for the maize flour and one for the wheat flour.

Near the window there is a stone sink under which the buckets with water are kept, finally a table with straw chairs and a bench complete the furnishings.

Into the environment

The peasant house was located outside the main residential nucleus, or in the districts that were born as a sum of rural houses, facing the pertinent farm overlooking or in the immediate vicinity, with the main openings facing south or west or to the east if conditioned by the orientation of the land upstream.

The planivolumetric relationship was only partially conditioned by the pertinence fund, as the houses were all small with a close family economy and were developed on the territory in a fairly uniform way to the development of the meadows or roncati (runcàcc) in possession of each family.

A distinction is mainly made between permanent dwelling houses, therefore with an adjoining housing system and located in places considered protected on the basis of historical memory, and those with temporary residence of farmhouses, characterized by a single multipurpose room, built for this function.

The houses were built with materials typical of the place: stones from the nearby quarries, wood from the surrounding forests, with the exception of the ridge, the root and the terzere made of fir and larch. The binder consisted of sand obtained from nearby streams and rivers, with a lime-based mixture normally obtained with the “calchére” procedure, once present in every place.

The Courtyard

In front of the house is the courtyard (èra or curt), from which in some cases, the access stairway to the upper floors rises and in the corner, carved out of a stone, a bench where one rested during a break.

The yard was generally paved with local stone slabs. Overlooking the farmyard, we find the storage for wood, work tools, and fresh stuff (serài) for the courtyard animals, the pigsty and the dunghill.

In the courtyards or under the portico, there was often the hearth at the service of several families; this was mainly used to heat water or milk, to do laundry or cheese. The hearth (foglà) is built with stones and lime mortar in a cylindrical shape, open at the front to put the firewood and on the side there is a sturdy wooden support (vicuna) to which the copper boiler was hung.

At other times the hearth was set up in a corner and the boiler was placed on a wrought iron tripod.

In a corner of the courtyard there was generally also the latrine and, to the side, the fountain, which was often at the service of the whole village or district.

The Groundfloor

The premises of the house were used for both humans and animals, gathered under the same roof. The rooms on the ground floor were generally intended as a stable built with a vaulted ceiling, a serciato floor (rés) and stone walls plastered with lime mortar.

In the stables, dairy and meat cattle were raised: cows, goats, sheep, pigs, rabbits, chickens, ducks and geese.

In most cases the stable opened directly onto the porch (pòrtech) open on the sunniest side of the house, with the function of hallway, storage for country tools and a workplace on rainy days. Other times we find a canopy (penzàna) with the same functions.

First Floor

Next to the stable or on the first floor was the kitchen with the fireplace. During the winter, people liked to stay in the stable, not only because it was warmer, but also for reasons of economy and savings.

The kitchen utensils most often used are: the clay pot (pignàta), the copper cauldron extended upwards for making cheese and laundry (perőlù) and for making polenta (perőlì); hanging from the fireplace (with the sòsta) or leaning on a tripod (tripé), the “pignàta” wider at the bottom for making soups, the “padèla”, the pan, the casserole, the “ramina”, the pan, the ” cògoma “of the coffee, the coffee pot, the coffee grinder (masnì), the wooden or iron milk bucket, the water and wine barrels, various copper containers, the terracotta jugs, mugs from terracotta, wood, tin or steel, glass bottles and flasks, demijohns, cutlery (pirù, cortél, cűgià), plates (la fundìna, ol piàt).

Directly from the kitchen, or else via a staircase, one entered the bedrooms. Also on the first floor, in front of the rooms or the kitchen itself, there was the loggia and on the open side, a structure of wooden poles to hang the bunches of corn to be dried (splère) and the sheaves of wheat were piled on the wooden floor .

From the loggia, or directly from the kitchen, through a wooden staircase or through a large door at the back, you enter the barn (fenèr) which generally reaches up to the roof.

The Second Floor

Upstairs was also often the children’s bedroom. In the attic (solèr) the disused objects were stored, since it was a good thing to keep everything that could one day be adapted or reused.

In front of the facades of the second floor there was the terrace (lòbia) which was used to dry the grains. In relatively recent times on the terraces, there was also the latrine in one corner.

Structure and Materials

The house was usually rectangular in shape, when it was built on sloping ground it was partially basement, made up of thick stone walls and lime mortar, with the ground floor having a vaulted ceiling (silter).

The upper floors were always with the perimeter walls of stone, rarely of wood, with attics consisting of a wooden structure with overlying planking.

The ceilings of the rooms were built with wooden beams with a planking above, while the dividing walls were built in wood or with a structure of wood and straw mixed with mortar.

The wooden-framed roof was covered with tiles or slates (piőde). Most of the ancillary buildings were built of wood with spruce bark cover (rősca).

The door and window openings were small and widened in the shape of a funnel inwards through rather thick walls, while in front of the windows on the ground floor there were often characteristic wrought iron railings for the evident purpose of defending the property.

Some houses belonging to more affluent owners, on the jamb of the stone entrance door bore inscriptions or dates or the coats of arms of the families were carved on them. The doors were made of wood, closed with bolts (scarnàs) from the inside or with characteristic locks.

The bedroom

Through a door you enter the room of the parents and the younger children. This room was furnished with a double bed with a horsehair (grìnga) or wool mattress, a chest for storing linen and clothes and sometimes, for the more affluent, there was a wardrobe and a dresser with a mirror, as well as a cot and cradle for younger children.

The sheets were made of linen and the pillow was filled with hen or goose feathers; the blankets were made of wool, for the wealthiest there was also a quilt, while for the poorest families these were obtained by sewing together all the pieces of fabric and rags that could be found (pelòcc) in several layers.

The children’s room was furnished only with the bed and the chest of drawers. Instead of the mattress there was the “paiù de scarfòi”, that is the leaves that wrapped the dried corn cobs and collected in a cloth, linen or hemp.

The children’s room was furnished only with the bed and the chest of drawers, instead of the mattress there was the “paiù de scarfòi”, that is the leaves that wrapped the dried corn cobs and collected in a cloth, linen or hemp.

Housework, Homemade Bread

The flour was obtained from cereals by pounding and grinding in the mill or by hand with a mortar and pestle of wood or stone. To make the bread, this was mixed with water, salt, yeast and then cooked.

The primitive ways of cooking were:

– grilling: the flour mixed with water and salt was placed on the embers of the hearth and was covered with burning ashes:

– other times the dough was placed in a bowl with a lid (the schisada).

– in many houses then there was the bread oven similar to the current pizza ovens.

The difference between the schiacciata and the bread is that the latter is obtained by cooking leavened dough. After mixing the flour with water and salt, the yeast is added which causes a fermentation process, which is why the dough grows. The yeast is obtained by keeping a small rest of the dough in a container, letting it sour.

The evening before baking, the yeast is mixed with hot water and flour and left in a warm place; during the night it rises and doubles in volume. Today brewer’s yeast is used. When the dough is well blended and leavened, loaves are made and cooked in the oven.

The laundry

The frequency of the laundry was seasonal and took from two to four days. The procedure was as follows: first the dirty clothes were soaked, that is, on the first day or the evening before, they were put in water and left to soak for a few hours in a special container. After soaking, the linen was soapy, washed a first time, rubbing it on the stone support or on the board (ass de laà); after soaping and the first wash, the linen was rinsed before being treated with lye (the actual wash).

The lye was obtained by adding suitable wood ash to the water. By mixing water and ash, potassium carbonate was obtained, the main effect of which was to remove the grease and soften the calcareous water, so as to make the soap treatment more effective. The most suitable water for washing was rainwater. The ash was boiled in the cauldron and the lye was poured repeatedly on the laundry, then boiled again.

The ash should never be placed in contact with the laundry, a coarse cloth was spread over it that served as a filter. The laundry was placed in the vat, a large wooden container in the shape of a truncated cone, formed by circled staves, with a hole at the bottom for the lye to escape. The laundry removed from the vat was soapy, washed, rinsed and squeezed by hand and then beaten onto stone slabs at the fountain or stream or on the washing board.

The pork

Pork was a major source of meat for the family and was mostly stuffed meat, so it would last a long time. Raising the animal with the remains of the kitchen was inexpensive and very profitable and provided tasty and varied food. As with the cheeses, the cold cuts were also produced locally and made according to the canons of tradition. The pig was killed with a stab in the heart, usually before Christmas.

It was like a party and the whole family took part in the event. Before the quartering, they were ready to collect the blood that was donated to the neighbors to make “la tùrta”. Then the bristles were cleaned with a sharp knife and boiling water. Then it was suspended and quartered into pieces, dividing the various parts: the lard, the bones from the meat, the entrails, the guts, which, well cleaned, were used to stuff the minced meat.

The meat was selected, minced, salted, spiced and finally stuffed into sausages to obtain salami and sausages (salam, codeghì, logànega). Lard and fats were used to make lard.

Another product that was obtained from the pig was the head, which was obtained after grinding the meat obtained from the head by boiling and stuffing.

The Farmer’s Work

The hay

The men mow the grass from 5 to 11 (saw the grass).

Behind them the women and children spread the grass with the two or three-pronged fork (spread the grass). After lunch the hay is turned over with a rake (ultà). In the evening there are several piles up to mt. 1,5 (muntù, muntunà). The next morning around 8/9, that is, after the sun has dried the soil of the night dew, they are scattered again; around noon the hay is still turned over, from 2 pm onwards it is usually brought to the hay with the “fraschéra” on the back.

Crops

The main crops are: potatoes, forage, alfalfa, maize (blue whiting), rye, wheat, oats, barley, buckwheat, flax and hemp.

Cultivation took place on a biennial or three-year rotation.

Method of working: the land is “aràt”, with the plow, or “angàt” with the spade or “zapàt” with the hoe. It is then leveled and cleaned with a shovel, a harrow, a rake or a wooden club, then sown by hand or with a sowing machine.

When the seedling emerges from the ground, earth is placed around the seedling (n’culmà) to form a longitudinal ridge.

The wheat harvest

Wheat was sown before Winter; reached maturity towards the end of August, they were harvested with a scythe (seghès), sheaves were made that were carried on the farmyard with the “fraschéra”.

The threshing by hand took place on the well cleaned threshing floor so that the beaten wheat would not be dispersed, with a double stick joined by a rope (fiàel), the sheaves were beaten to divide the straw from the wheat. Once the straw was removed with a rake, the grain had to be separated from the chaff. The latter operation took place by ventilation or by drilling.

La Rasga del Tönöla

A very rare example in the entire province of Bergamo, the Rasga del Tönöla consists of an ancient original eighteenth-century sawmill in the locality of Valcanale, powered by water, renovated and fully functional.